By Rachel Gass – 6/27/25

The Case for Restructuring Global Climate Finance

Responsibility for Climate Disaster

Wealthy nations contribute disproportionately to global climate emissions, with the United States as the largest historical emitter of CO2. What do these emissions mean in terms of responsibility for today’s climate breakdown, and how should that responsibility shape global climate action?

A new study released in the UK is the first to directly quantify this link. Using wealth-based emissions data, researchers subtracted the emissions of the wealthiest 10%, 1%, and 0.1% to model changes to the climate that would have occurred without them. They then compared these scenarios to actual climate outcomes to calculate each group’s responsibility for the climate crisis.

The researchers found that 65% of the increase in global mean temperature between 1990 and 2020 could be attributed to the world’s richest 10%. The wealthiest 0.1%, while making up less than one-one hundredth of the global population, bore 8% of the responsibility for global warming. These findings—that the world’s wealthiest are responsible for two-thirds of global heating since 1990—are a powerful argument for international finance to support countries hit hardest by climate disasters they can least afford and did little to cause.

The State of Global Climate Finance

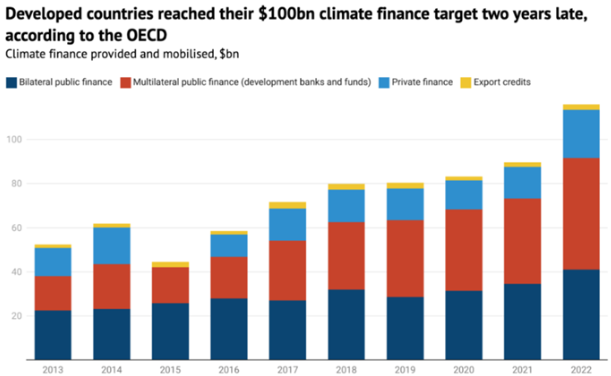

At the 15th Conference of Parties in 2009 (COP15), developed countries reached a landmark agreement to provide $100 billion USD per year by 2020 for climate action in developing countries. Participating nations extended the climate finance target through 2025 at COP21 in Paris. However, total climate finance only reached $83 billion by the 2020 deadline, falling $17 billion short. It wasn’t until two years later, in 2022, that developed nations achieved their stated goal, contributing approximately $106.8 billion or $115.9 billion, according to two different estimates.

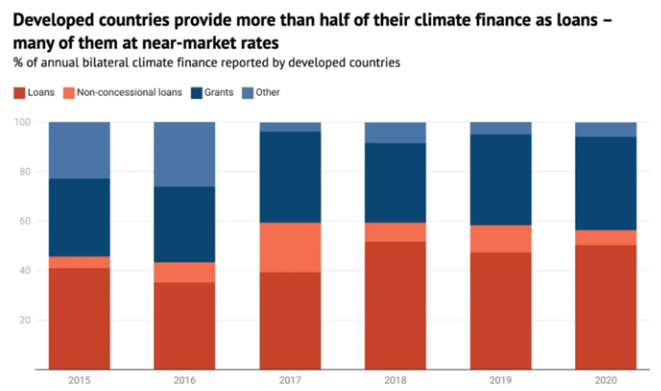

These funds consisted primarily of bilateral country-to-country aid ($44.2 billion per a Center for Global Development estimate), multilateral climate funds ($46.2 billion according to CGD), and private sector finance. Sixty nine percent of total public finance was provided as loans.

Source: Carbon Brief

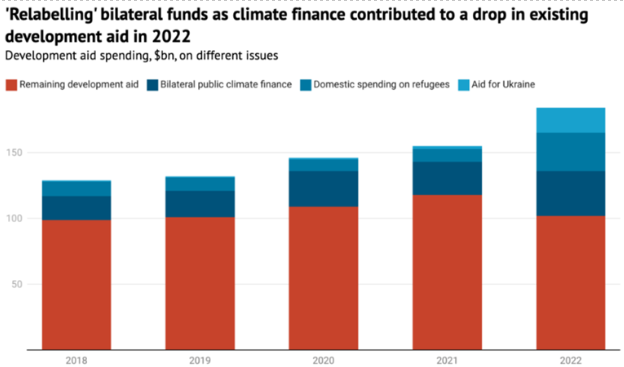

Across both bilateral and multilateral providers, as much as over one-third came from refocusing or rebadging existing finance, meaning that, despite stipulations in the 2009 Copenhagen Agreement that funding be “new and additional,” less than two-thirds of climate finance in 2022 could be considered so. In practice, this work-around meant that, instead of contributing additional climate finance, countries used accounting changes to reach climate targets while at the same time slashing their wider aid budgets. Judged as a share of provider economies, total development finance fell slightly, suggesting no true additional fiscal effort.

Source: Carbon Brief

Advocates expressed concerns that as countries increasingly announce major cuts to their foreign-aid budgets, contributions to climate finance will drop in suit, making achieving climate finance goals more challenging. Thus far, the UK, Switzerland, Germany, France, and the Netherlands have cut as much as 37% of their aid budgets, adding up to nearly $40 billion, the effects of which will reverberate into the global climate finance pool.

Even as wealthy countries have slashed their foreign aid budgets, they have re-upped their support of climate resilience in developing countries, committing $300 billion annually with a cumulative goal of at least $1.3 trillion by 2035. This figure triples the $100 billion per year target to continue helping vulnerable nations curb carbon emissions and adapt to the crippling effects of climate change. However, amid drastic budget cuts, whether countries will reach these new targets remains in question.

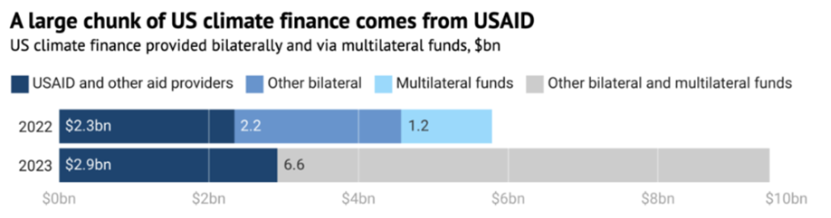

U.S. Financial Contributions

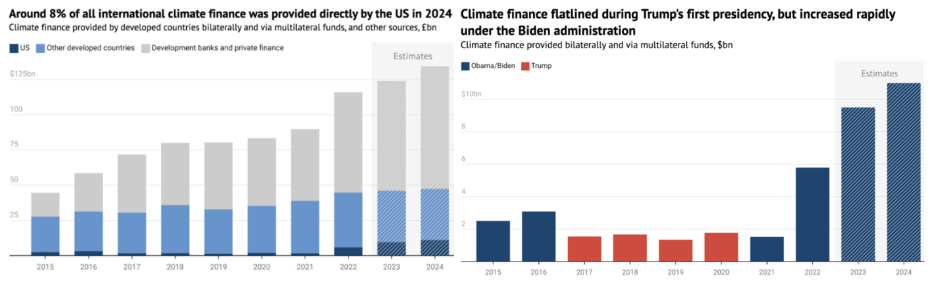

From 2020 to 2024, the U.S. share of climate finance contributions quadrupled from 2% to over 8%, with the $11 billion commitment in 2024 representing a seven-fold increase over the course of President Joe Biden’s term.

Source: Carbon Brief

Despite these promising contributions, in recent months, the U.S. has significantly backtracked on its commitment to a multilateral approach to the climate crisis. One of President Trump’s first Executive Orders was to withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, the landmark 2015 treaty to limit global warming below 1.5C. He proceeded to cut global climate aid, including $3 billion from USAID and $4 billion from the UN Green Climate Fund. These cuts threaten critical programs like SERVIR, an early-warning system that has saved hundreds of thousands of lives by providing advance alerts before weather-related catastrophes hit.

Cuts to USAID mark a big blow to global climate finance efforts, as USAID is grant- rather than loan-based, which experts agree is superior at supporting climate adaptation in developing countries. A large chunk of remaining climate finance from the U.S. now comes from the International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), which committed more than $3.7 billion in 2023 and 2024. The DFC’s investment in private enterprises does not suit global climate finance, though, because it shifts funding away from public needs towards U.S. commercial interests (i.e. what benefits U.S. corporations rather than frontline communities).

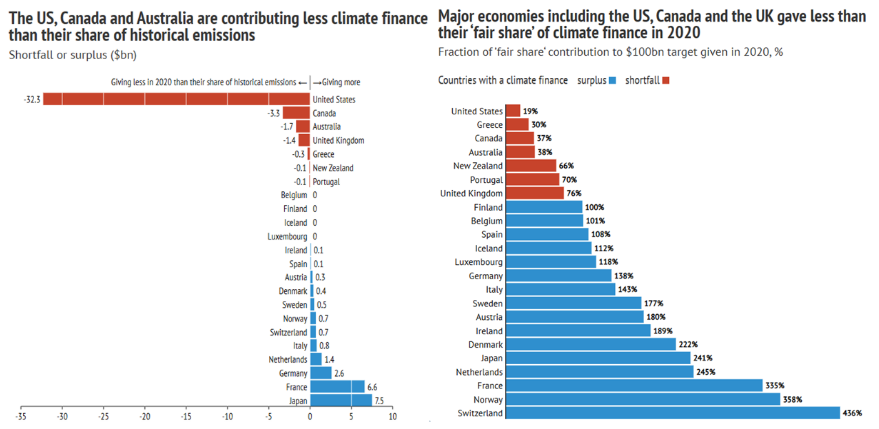

Source: Carbon Brief

Recent aid cuts put the U.S. further behind its “fair share” of climate finance contributions. The U.S. ranked as only the fourth largest provider of international climate finance in 2024, a position that has only dropped since severe foreign aid cuts. Studies show that, according to its wealth and responsibility for climate change, the U.S. should have paid nearly $40 billion towards the former $100 billion climate-finance target, $29 billion more than the estimated $11 billion it gave in 2024. This means that, to reconcile its share of responsibility for the climate crisis, the U.S. must significantly ramp up its contributions to climate aid.

Source: Carbon Brief

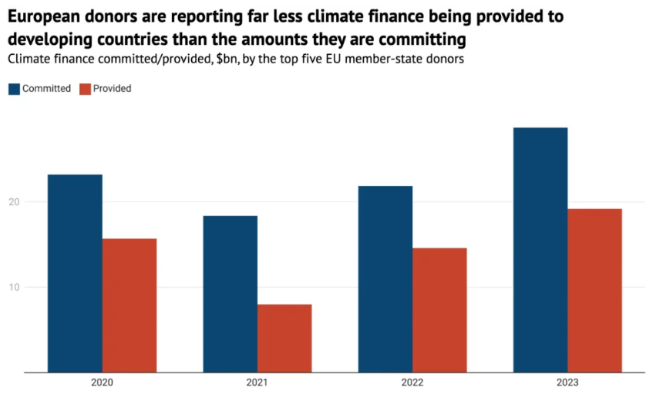

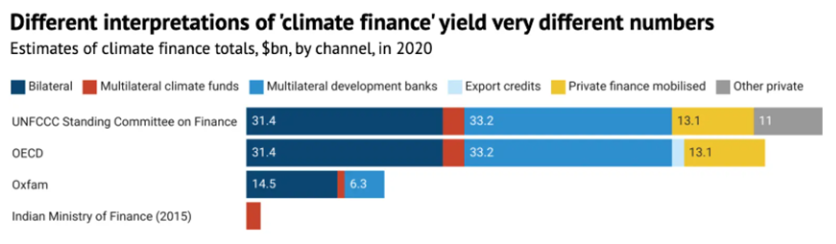

Complications to Global Climate Finance

Part of what makes equitable global climate finance so difficult to achieve is the current system’s lack of transparency and tracking standards. No agreed-upon definition of what counts as climate finance exists, making assessing whether annual goals are met difficult to impossible. Each government reports funds as climate finance differently depending on its priorities and policies; most governments, for instance, count 100% of projects where climate is a “principal” objective but report only 30-50% of projects where climate is deemed “significant.”

Countries register their bilateral contributions in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Creditor Reporting System (CRS) and use this data to guide what they report as “official” climate finance to the UN. OECD has no power to amend projects that have been marked incorrectly, nor does the organization provide a breakdown of contributors. Citizens have little access to information about how governments use public climate funds, including whether they are even used for projects relevant to tackling climate change. And, governments are not obligated to report any cancellations or changes in funding, meaning that reported money may never be spent, even if listed “planned” or “committed.”

Source: Carbon Brief

As a result, the total yearly contributions can be overinflated—Carbon Brief identified at least $6.5 billion attributed to projects involving coal, oil, and gas that had been marked as climate-related in the OECD’s database between 2012 and 2021. In another study, ONE Campaign found that, of the $616 billion climate-related aid reported to OECD committed since 2013, $69 billion of disbursements were missing data, and another $228 billion had not yet been disbursed. More effort must be put into tracking disbursements to ensure that climate finance achieves its intended goals.

Source: Carbon Brief

Loan-based debt poses another significant barrier to achieving climate resilience in developing countries by overstating finance flows. Over half of the bilateral finance committed by developed countries and 75% of investments by multilateral development banks (MDBs) come in the form of loans. Unlike grants, loans must be paid back with interest, generating profit for contributor countries while deepening debt for developing ones. This dynamic is particularly troubling given that the largest contributors to climate finance provide most of their support as loans, thereby profiting from the vulnerabilities they had the most responsibility for creating. Faced with limited alternatives, developing countries have few options but to depend on these loans.

Source: Carbon Brief

An analysis of the 58 countries with available data from the Least Developed Countries (LDC) Group and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) group, home to a combined 1.2 billion people, found that most climate-vulnerable countries spent more than twice as much repaying loan debts than they received in climate finance in 2022. Almost half of these countries are at high risk of defaulting or are in debt distress, hampering their abilities to invest in climate resilience, the exact challenge climate finance intended to address.

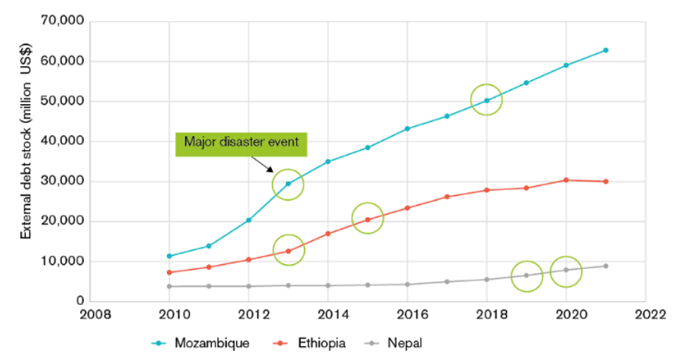

This debt crisis is especially concerning because LDCs and SIDS tend to be the most exposed to climate impacts with the littlest amount of fiscal room to adapt. Major climate events push climate-vulnerable countries into vicious cycles of borrowing to rebuild their infrastructure, further compounding their debts to countries that have contributed much more to the climate crisis to begin with.

The amount of actual and promised climate finance, while increasing, is not keeping pace with debt payments. In 2021, the poorest and most climate-vulnerable countries paid $33 billion on debt servicing while only receiving $20 billion in climate finance, meaning that developing countries continue to get pushed into the negatives, hampering their capacities to handle subsequent and worsening crises.

Source: International Institute for Environment and Development

Accounting for how much developed-country governments subsidize climate loans, the actual value of total climate finance in 2022 was closer to between $28 to $36 billion, meaning that, in real terms, developed countries have yet to achieve their $100 billion annual finance goal.

The Future of Global Climate Finance

Among other changes, providing effective climate finance requires increasing aid proportionally to nations’ responsibility for climate change, restructuring finance tracking, and rethinking debt. One possible solution is debt-for-nature swaps, which forgive part of a nation’s debt in exchange for achieving specific, measurable outcomes in climate or nature projects. 2022 public external debt stocks from the International Monetary Fund/World Bank show that of the over $431 billion that the 49 countries most at risk of defaulting on their external debt collectively owe, $103.4 billion can be freed up using swaps. For LDCs specifically, swaps could free up to $33.7 billion, significantly more than the $6.1 billion they received in climate finance in 2021. Such swaps have been successfully deployed in Cabo Verde, Ecuador, and Belize. Other solutions include debt suspension, parametric insurance, and more long-term options.

To escape the climate-finance doom loop, global climate actors must listen to leaders from nations on the receiving end of climate finance and consider debt justice. It is only then that global climate finance can achieve its critical goals of addressing responsibility for the climate crisis and protecting the most vulnerable nations from its most devastating effects.